Miroslav, Micolaii, Danilo, and Micolaii died as soldiers fighting for Ukraine

A Time for Remembrance

Military Requiem for the Soldiers of Kramatorsk

Drawing closer to the front means drawing closer to those who fight—and those who fall. Commemorations allow families and soldiers to remember their loved ones. Attending a military requiem is a way to bear witness to their loss, their grief, and their longing for justice.

The fourth-floor hospital hall is simple: tiled floor, faded beige walls, one door to the stairs, another to the elevator. Half-separated from the hospital corridor by two white wrought-iron gates, it becomes a room of its own. Through white curtains, the pale light of a cloudy day falls on a table. Four photos are arranged there—four faces of soldiers: Miroslav, Micolaii, Danilo, and Micolaii—all fallen for Ukraine.

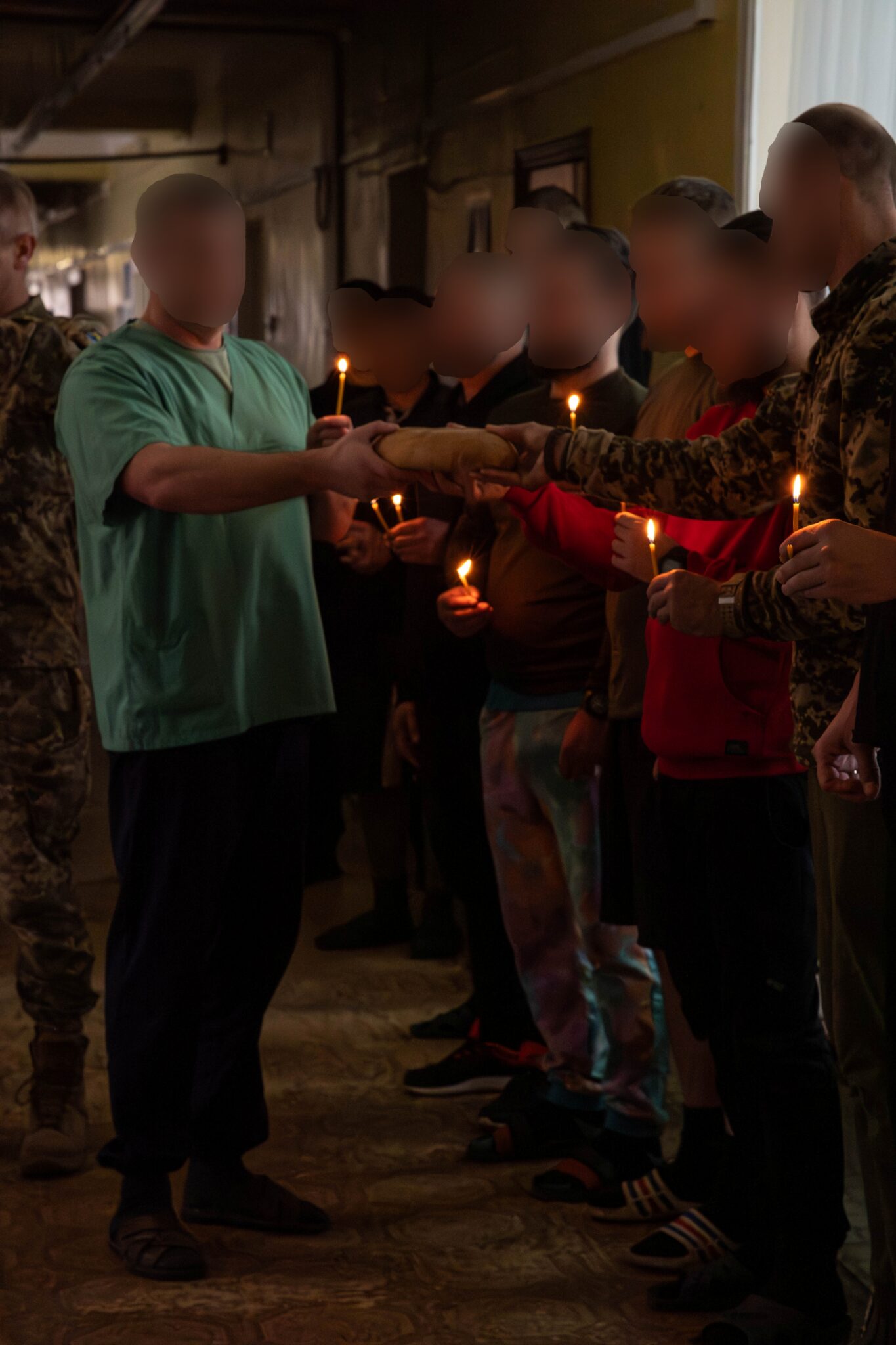

Gradually, the gathering forms, pressed against a wall of the hall and into the corridor. Each person takes a candle as the cleric stands before an improvised altar. In front of the gold of a survival blanket, a photo of the Virgin sits among the host and candles. Wearing a green tunic, the military color contrasts with the stole in the colors of the Ukrainian flag.

The panikhida, an Orthodox requiem, is a slow, grave chant that resonates in the silence of the hospital corridor. The faithful, standing in the Eastern rite, listen to the chants, incantations, and speeches to the dead.

The entrance hall of the fourth floor has been arranged so as to permit the religious ceremony.

Far from the traditional splendor of Orthodox churches, the soldiers commemorated their dead simply today. “The pastor of the ceremony is from the same village as my husband,” explains Ivanna. The widow of Micolaii, whose photo is on the table, initiated the ceremony. Three other families joined her, their loved ones’ photos also on the table.

“It’s simpler this way,” Ivanna continues. “The graves are scattered, and doing this at the hospital (where Ivanna knows the staff) suits everyone.”

Before the ceremony, other soldiers added the names of their fallen comrades to the diptych of the dead; about thirty were mentioned.

Ivanna, widow of Micolii, is holding a cake for the shared meal after the ceremony.

After the requiem, the secular ceremony continues in an adjacent room. Traditionally, Ukrainians commemorate their loved ones with a banquet. On the tables are plates of ‘salat’ (Ukrainian salad) and pieces of meat.

Apart, Taras, an infantryman of the 10th Mountain Assault Brigade, remembers Micolaii, who died two years ago. “I’m a conscript,” the soldier explains, “we met at training camp in 2022.”

Taras, a short bald man with a muscular build, sports a short, thick beard framing his jaw. His voice is steady, his gaze stoic; only the tightening of his throat, as memories surface, betrays the void left by Micolaii’s death.

“He was smart, always ready to help others,” says the soldier, sitting in the hospital hall. In training, conscripts had to learn the basics of soldiering—a profession they were not destined for. “Some struggled to understand. But Micolaii was quick to advise. He grasped things fast. He helped me a lot, actually,” recalls Taras.

It was under fire that Micolaii and Taras sealed their friendship. First deployed to the fourth line for two months of “acclimatization,” their task on line zero was to build new positions for their unit. “We had to dig ‘blindages’—reinforced positions—and trenches,” explains Taras. Isolated and separated by 20 meters, Micolaii and Taras communicated by shouting and radio. “During bombardments, it helped us not feel alone,” the soldier relates.

Recognized for his coordination and combat medicine skills, Micolaii was often called upon by command. “One day, with Micolaii, we evacuated four wounded from the positions,” remembers Taras. From the front line, the two soldiers had to retreat several kilometers on foot to find a civilian vehicle in the third line. “Then we went back to line zero to get everyone out,” says Taras.

After the shared meal and speeches, two soldiers walked down the lane of the hospital.

In 2023, Taras and Micolaii were sent to the Yakovlivka sector, north of Barkhmout, where the siege was raging.

“Micolaii was in another position with a comrade when a tank targeted them,” Taras recounts. He himself was nearby with two other soldiers, while his friend’s position came under direct fire from a Soviet T-72, a 42-ton machine. Taras heard Micolaii’s comrade on the radio: “He took shrapnel to the head—the wound is fatal.”

Taras’s colleagues left their position to join “Sunflower,” Micolaii’s position, to help extract the body. Taras stayed put. “I don’t know how to describe what it’s like to lose a friend,” says Taras. “The emptiness it leaves is ineffable,” the soldier concludes, eyes slightly moist.

The day after Micolaii’s death, artillerymen avenged their friend in their own way. On their 120mm shell, the mortar crew wrote “for Micolaii.”

Ivanna, with a photo of her husband, is holding an FPV drone that was provided by the mourning families.

Two years after his companion’s death, Taras reflects on losing comrades in battle. Despite the habit, “it’s not something you can ever prepare for,” comments the soldier.

For the rest of the gathering, too, the pain remains sharp. At the foot of the table, near the photos, lies an FPV drone. “This one’s for the Russians, for our loved ones they killed,” explains Ivanna. “It’s for my husband; this drone will kill some Russians.”

At man’s height, between the lines — Little Frenchy

Article's gallery

Soldiers and family members holding taper candles in the corridor of the hospital.

Koliva, the offering of the bread

Koliva, the offering of the bread

Orthodox priest, downing a stole to the colors of Ukraine above his chaplain’s green tunic.

Ivanna, talking about her husband next to the portrait of an anonymous soldier.

At man’s height, between the lines — Little Frenchy

22/12/2025